|

| Buy F&SF • Read F&SF • Contact F&SF • Advertise In F&SF • Blog • Forum |

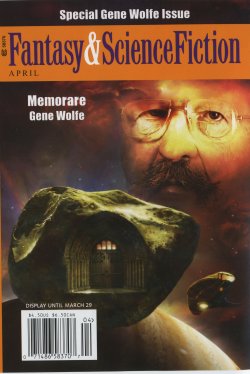

April 2007

|

Memorare THE MOMENT MARCH Wildspring spotted the corpses, he launched himself across the shadowy mortuary chamber. He had aimed for the first, but with suit jets wide open he missed it and caught the third, flattening himself against it and rolling over with it so that it lay upon him. Bullets would have gotten him; but this was a serrated blade pivoting from a crevice in the wall. Had it hit, it would have shredded his suit somewhere near the waist. He would have suffocated before he froze. The thought failed to comfort him as he huddled under the freeze-dried corpse and strove not to look into its eyes. How much had his digicorder gotten? He wanted to rub his jaw, but was frustrated by his helmet. Not enough, surely. He would have to make a dummy good enough to fool the mechanism, return with it, and.… Or use one of these corpses. "Remember, O most gracious Virgin Mary, that never was it known.…" The half-recalled words came slowly, limping. "That anyone who fled to your protection, implored your help, or sought your intercession, was left unaided." There was more, but he had forgotten it. He sighed, cleared his throat, and touched the sound switch. "These memorials can be dangerous, like this one. As I've told you, this isn't the big one. The big one we call Number Nineteen is an asteroid ten times the diameter of this, which means it could have a thousand times the interior volume. Frankly, I'm scared of it. We may save it for last." He had a harsh, unpleasant speaking voice. He knew it; but it was the only voice he had, and the software that might have smoothed and sweetened it cost more than he could afford. Back on his hopper, he would edit what he had said into a script for Kit. She had a voice.… "There are at least five sects and cults whose members believe the deceased will be served though all eternity by those who lose their lives at his or her memorial. Some claim to be offshoots of major faiths. Some are openly satanic. We haven't seen enough to identify the bunch that built this one, and frankly I doubt we will." If the show sold, if it made one hell of a lot of money, it might—it just might—be possible to buy or build a robotic probe. Of course, if that probe were destroyed.… He began wiggling out from under the corpse and sliding under the next. Nothing happened. "Memorare.…" He had read the Latin twice, perhaps. It was as lost as the English now. No, more lost. The blade was set to rupture the suit of anyone who came in. That much was plain. What about going out? When he had the first corpse steady and vertical, a gentle shove sent it across the chamber in a position that looked practically lifelike. Nothing. No blade, no reaction of any kind as far as he could see. Possibly, the system (whatever it was) had detected the imposture. He tried to make the second corpse more lifelike even than the first. Still nothing. What if a corpse appeared to be entering? A few determined pulls on his lifeline got him plenty of slack. Hooking it to the third corpse, he held the thin orange line with one hand while he launched the corpse with the other. When it had left the memorial, a gentle tug brought it in again. The blade flashed from its crevice, savaged the corpse's already-ruined suit, and flung the corpse toward him. "You've got a new servant," March muttered, "whoever you were." Playing it safe, he went out the way he had come in—fast and high. Outside, he switched on his mike. "We just saw how dangerous a small percentage of these memorials are, a danger that poisons all the rest, both for mourners and for harmless tourists who might like to visit them. A program for identifying and destroying the few dangerous ones is badly needed." Propelled by his suit jets, he circled the memorial, getting a little more footage he would probably never use. His digicorder had room for more images than he would ever need. Those millions upon millions of images were the one thing with which he could be generous, even profligate. "Someone perished here," he told the mike, "far beyond the orbit of Mars. Other someones, employees or followers, family or friends, built his memorial—and built it as a trap, so that their revered dead might be served.… Where? In the spirit world? In Paradise? Nirvana? Heaven? "Or Hell. Hell is possible, too." Flowing letters, beautiful and alien, danced upon the curving walls. Arabic, perhaps, or Sanskrit. It would be well, March thought, to show enough of it that people would recognize it and stay away. For the present, the corpses floating outside it might be warning enough. His digicorder zoomed in before he switched it off and returned to his scarred olive-drab hopper. There was an Ethermail from Kit when he woke. He washed, shaved, and dressed before bringing her onto his screen. "Hi there, Windy! Gettin' lonely out there in the graveyard?" She was being jaunty, but even a jaunty Kit could make his palms sweat. "Well, listen up. Have I got a deal for you! You get me to em-cee this terminal travelogue you're makin'. As an added bonus, you get a gal-pal of mine. Her name's Robin Redd, and she's a sound tech who can double in makeup. "What's more, we come free! Absolutely free, Windy, unless you can peddle your turkey. In which case we'll expect a tiny little small cut. And residuals. "So whadda you say? Gimme the nod quick, 'cause Bad Bill's pushin' me to come back. Corner office, park my hopper on the roof with the big boys, and the money ain't hopscotch 'n' hairballs either. So lemme know." Abruptly, the jauntiness vanished. "Either way, you've got to be quick, Windy. Word is that Pubnet's shooting something similar out around Mars." He said, "Reply," and took a deep breath. It was always hard to breathe when he tried to talk to Kit. Yes, even when she was three hundred million miles away. "Kit, darling, you know how much I'd love to have you out here with me, even if it were just one day. I want you and I want to make you a superstar. You know that, too." He paused, wishing he dared cough. "I couldn't help noticing that you didn't mention what Bad Bill wanted you for. Knowing you and knowing that there isn't a smarter woman in the business, I know you've found out. It's his pet cooking show again, isn't it? He wouldn't give you a corner office for those kiddy shows, or I don't think he would. "So get yourself one of the new semitransparents, okay? 'Vaults in the Void' is just about roughed out, everybody in the world is going to want to see it by the time we're finished with it, and nobody who sees it will ever forget you, darling. "God knows I won't." He moved his mouse and the screen went dark, leaving only the faint reflection of an ugly middle-aged man with a crooked nose and a lantern jaw. The on-board had found three interesting blips strung out toward the orbit of Saturn, but Jupiter—specifically the mini-solar system surrounding it—was closer, and every hop took its toll of his wallet. He put the Jovian moons on screen and began speaking, just winging it so as to have something to work over for Kit later. "Mightiest of all the worlds, Jupiter has drawn travelers ever since hoppers became a consumer necessity. When the first satellite was launched in nineteen fifty-seven, the men and women who put it into orbit could hardly have dreamed that Luna and Mars would be popular tourist destinations in less than a hundred years. Nor could the pioneers who built the first hotels and resorts there have anticipated that as soon as translunar travel became popular, travelers seeking more exotic locales would come here to the monarch's court. "You've got to throw a lot of money in the hopper. That's for sure. But that only makes it that much more attractive to those who've got that money and want to flaunt it. It's dangerous, too—transmissions from tourists whose icoms go abruptly silent make that only too clear, and every edition of the Solar Traveler's Guide strives to make the danger a little plainer. "Unfortunately, the striving doesn't seem to do much good. People keep coming, alone or in company. Sometimes they even bring children. Every year, five, or ten, or twenty don't make it back. Do all of them get memorials in space, memoria in aeterna? No, of course not. But many do, and such memorials are becoming more popular all the time. Some are simple stones. Others—well, we'll be showing you a few. In an age in which the hope of a life after death gutters like a candle burned too long, in a century that has seen Arlington National Cemetery bulldozed to make room for more government offices, the desire to be remembered leaps up with a bright new flame. "If not remembered, at least not totally forgotten. We wish it for our loved ones, too. We'd like some spark of them to remain until the sun grows dim. And who can blame us?" Now to make the hop. Perhaps he would learn, soon, just what had happened to that poor girl who had tried, for so short a time, to raise her sweetheart and his friends. The first memorial he checked was a beautiful little thing. Someone with taste had taken a design intended for the desert and reworked it for space, with no up and no down, a lonely little mission shrine not too near Jupiter that reached up for God in every direction. The bright flames inside belonged to votive candles, candles that burned in vacuum, apparently because their wax had been mixed with a chemical that liberated oxygen when heated. They made a glorious ring of white wax and fire around the shrine, burning in nothingness with fat little spherical flames. "A shrine sacred to the memory of Alberto Villaseñor, Edita Villaseñor, and Simplicia Hernandez," he told his digicorder, "placed here, deep in space, by the children and grandchildren of the Villaseñors and the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Simplicia Hernandez." How many thousands of hours had Al Villaseñor labored under a broiling sun before he could buy the hopper that had carried him, with his wife and the very elderly woman who had probably been his mother-in-law, to a death somewhere near Jupiter? Their 3Ds were in the shrine; and the mark of those hours, of that sun, was on Al's face. Turning off the audio, March murmured a prayer for all three. Back on his hopper, clicking Ethermail got him Kit's blue eyes and bright smile. "What's this 'semitransparent' bull, Windy? Transparent's only a couple thou more. I've got a good one, and I've been posing for the mirror. No picky-picky underclothes underneath. Wait till you see the pix! You're gonna love 'em. "But Windy, you didn't say a thing about my li'l pal Robin Redd. Can she come, too? I gotta bring her, Windy, or not come myself. She's on the lam from a ex who beats hell out of her. She's got an Order of Protection and all that crud, which he doesn't give a rat's ass about. I know he doesn't, Windy. I was with her on Wednesday when he kicked her door down. Scout's honor! I grabbed the carving knife and screamed my cute li'l head off. "Windy, honeybear, I can't leave Robin high and dry. I won't! Not after what we went through Wednesday night. So can she come? It's me, Windy. This is Kit, and I'm begging." March sighed and leaned back in the control chair, collecting his thoughts before he spoke. "Gee, Kit, here I thought you were longing for the sight of my manly profile. Okay, I've got it now. Bring your friend. I trust she's too well-mannered to push back the curtain when she hears funny noises from a bunk. Trust me, I'll wash the sheets this time. "But Kit, you're going to have to wear something under that see-through suit. Get used to the idea if you want me to show you below the neck." AS MARCH EDGED his hopper just a little nearer Number Nineteen, he turned up a new memorial, an asteroid circling Jupiter well outside the orbit of Sinope. Earlier he had thought it only a rock, a piece of pocked debris too small to hold even the chips knocked loose by meteorites. Now he could see the entrance of the tomb. It was closed, though most such entrances gaped open, and square, though most were rough circles. As he zoomed in on the tumbling asteroid, the neat lettering before that entrance grew clear: PLEASE WIPE YOUR FEET. This was one he wanted. His own suit, orange and strictly opaque, was starting to show signs of wear. Nothing dangerous yet, but it would have to be watched. A military suit.… Well, a military suit wore pretty much like armor. A military suit got rid of built-up heat and kept the wearer warm no matter what. The wearer could relieve himself right there in his suit, and eat and drink whenever eating and drinking seemed necessary or advisable. Three kinds of lights, a score of tools, and half a dozen weapons were built into the suit; so was a mini computer with enough capacity for a whole lot of AI. That little on-board could and would offer warnings and advice. It would watch the wearer's back and even stand guard while he slept. A soldier in a military suit could reach up into his helmet and pick his nose, or even take a suitless comrade—wounded or otherwise—into the suit with him. A military suit.… Cost more than March Wildspring had been worth before his divorce, and twenty times more than he was worth at the moment. His own space suit, this dull orange suit that was beginning to show wear, provided propulsion, communication, and breathable air for four hours plus. Little more beyond a fishbowl helmet that would darken when hit with a whole lot of ultraviolet light—Twentieth Century tech, and he was lucky to have even that. Shrugging, he closed his suit and buckled on his utility belt. Spaceboots over the feet of the suit were not strictly necessary, but were (as March reminded himself) a damned good idea. Suits tore. Cheap civilian suits tore pretty easily, and tore most often at the feet. Small permanent magnets in the boots would keep him on the sheet-metal body of his hopper without holding him there so tightly that he would have trouble kicking off. With the second boot strapped tight, he hooked his lifeline to his belt and put on his helmet. On Earth, his suit weighed fifty-seven pounds. Here it weighed exactly nothing; even so, his irritated struggles against its frequently pigheaded mass provided a good deal of useful exercise. People tended to get soft in space. Kit would be another source of salutary exercise, he reflected, if things went as well as he hoped. The airlock was big enough for one person in a pinch, if that one person was mercifully free of claustrophobia. March shut the inner door and spun the wheel, listening to his precious air being pumped back into the hopper, to its whispering, whimpering departure. Then to silence. Fifteen seconds passed. Half a minute, and the outer door swung back. He kicked off from the inner door and turned on the suit's main jet. Steering jets and seat-of-the-pants flying kept him on course for the asteroid into which some unlucky tourist's tomb had been carved, and enabled him to match the asteroid's rotation. The inscribed welcome mat before the door was, on closer inspection, wrought iron. His boots stuck to the iron nicely. Was he to knock? He did, but there was no response. Presumably there was no atmosphere inside the tomb, but it would have been possible—even easy—for a mike to pick up sound waves transmitted through the stone walls. Checking a third time to make certain his digicorder was running, he searched the doorframe for a bell button and found one. The wood-grained steel door opened at once, apparently held by a bald, pleasant-looking man of about sixty. "Come in," the bald man said. He wore an old white shirt and faded jeans supported by red suspenders. "It was darned nice of you to come way out here to see me, son. If you'll just come inside and sit down, we can have a good chat." March switched on his speaker. "I'll be happy to, sir. I know you're really a holographic projection, but it's very hard not to treat you as living person. So I'll come in and chat, and thank you for your hospitality." The bald man nodded, still smiling. "You're right, son. I'm dead, and I'd like to tell you about it. About my life and how I came to die. I'd like to, but if you don't want to hear it, I can't keep you. Will you stay and make a poor old dead guy happy?" "I certainly will," March said, "and half the world with me." He indicated his digicorder. "Why that's wonderful! Sit down. Sit down, please. I hate to keep my guests standing." It was just possible that there were knives that would slash his suit concealed in the fluffy pillows of the sofa behind the long coffee table. March chose what appeared to be a high-backed walnut rocker instead, tying its cord so that he floated a few inches above its seat. The bald man dropped into an easy chair that showed signs of long use. "I'd make you some iced tea if you could drink it, but I know you can't. It doesn't seem right not to offer a guest something, though. I've got some little boxes of candy you could take back to your hopper. Maybe give to the missus, if she's in there? You like one?" March shook his head. "She's not, sir. It's very kind of you, but what I'd really like is to hear about you. Won't you tell us?" "Happy to, son. Glad to recite my little adventures, at home and out here in space. Frank Welton's my name, and I was born in Carbon Hill, Ohio, U.S.A., one of a pair of twin boys. Probably you never heard of Carbon Hill, it's just a little place, but that's where it was. I was a pretty good ball player, so I played ball for eight years after high school. See my picture? The kid with the glove and bat?" The bald man pointed, and March swung his digicorder to get it. "That was taken when I played for the Saint Louis Cardinals. I played left field, mostly, but I could play all three outfield positions and I generally hit pretty close to three hundred. The money was good, and I meant to stay in baseball as long as I could. That turned out to be eight seasons, but for that last season I was a pinch hitter, mostly. An outfielder has to have a good strong throwing arm, and my shoulder blew out on me." March said, "I'm sorry to hear that, sir." "Well, I got out of baseball and went home to Carbon Hill. A friend of my dad's was in the sand and gravel business in a small way. He was getting on and wanted a younger partner with some money they could use to expand the business. I threw in with him, and when he died I bought his widow out. Pretty soon I was making more in sand and gravel than I ever had playing ball. I got married.…" The bald man took out a handkerchief and dabbed at his eyes. March cleared his throat. "If this is too painful for you, sir, I'll go." "You stay, son." The bald man swallowed audibly and wiped his nose. "There's things I got to tell you. Only I got to thinking about Fran. She died, and I didn't have the heart anymore. Business is like baseball, son. If you got nothing but heart, you can still win on heart. Not all the time, mind, but now and then. That's what they say and it's the truth. But if you don't have heart, you're done for." March nodded. "I understand you, believe me." "That's good. I turned the business over to our kids. That's Johnny, Jerry, and Joanie, and they're the ones who built this memorial for me. They owed me a lot, and they still do. But they paid off a little part of what they owed with this. Like it?" "One of the best I've seen, sir, and I've seen quite a few." "That's good. I bought me a hopper when I retired. I told everybody I wanted to see Mars because of all the sand and gravel they had there. I thought it was true, but what I really wanted was to get away from Earth. Maybe you know how that is." March nodded. "So I did. Spent a little time on Mars and a few days on the moon, then I thought I'd have a look at Ganymede, Callisto, Titan, and so forth. The big satellites of the outer worlds, in other words. People don't realize how many there are, or how big they are, either. "It was Io that did me in. Not the li'l gal herself, but trying to get there. Oh, I knew all about old Jupiter. How far out his atmosphere goes, and the radio bursts. All that stuff. What I hadn't figured on was just what all the gravity meant. Just how quick it grabs you, and how quick a hopper heats up when it hits ol' Jupiter's atmosphere. I guess I've 'bout talked your ears off now." March shook his head. "If you've got more to say, sir, I'll listen." "Then I'll say this. My dad was a good man and a hard worker, but he was a day laborer all his life, and he died at fifty-four. Go back a few generations, and my folks were slaves. I had a better life than my dad did, and one hell of a lot better life than they did. I'd like a prayer or two, son, and I'd like to be remembered. But I'm not complaining. I got a fair shake, and I had a lot of luck. Want to see how I looked when I was dead, son?" "I don't understand how that's possible, sir." March hesitated before adding, "You were pulled down to Jupiter, and your hopper must have been burned away completely before it hit the planetary surface." "Well, son, I can show you just the same. This is pretty slick, so have a look." Leaning forward the bald man touched the top of the coffee table, and it became as transparent as glass. A dead man lay just below the transparent surface, his eyes shut and his hands folded. His white shirt and casual jacket were well-tailored and looked expensive. After studying his features, March said, "That's you all right, sir. Computer modeling?" "Nope." The bald man had turned serious. "It's an actual tridee, son, taken at the funeral. That's my twin brother, Hank. He died forty-six days after I did. That happens a lot with twins. One gets killed and the other dies. Identical twins I mean. Which is what we were. Nobody knows why it happens but it does. Hank turned in for the night like usual. Barbara went to get him up in the morning, and he was dead. You want to be dead, son?" March shook his head. "No, sir. I don't." "Then you take a lesson from me and watch out for that ol' Jupiter."

| |

|

| ||

To contact us, send an email to Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Copyright © 1998–2008 Fantasy & Science Fiction All Rights Reserved Worldwide

If you find any errors, typos or anything else worth mentioning,

please send it to sitemaster@fsfmag.com.